- Home

- Addison Jones

Wait For Me Jack Page 2

Wait For Me Jack Read online

Page 2

The tears obeyed; as quickly as they’d welled, they vanished. He went back to his pill popping. An idea occurred to him, while she and her whiff moved past. He held his head still to prevent the idea from sloshing out his ears, nose or mouth. He wasn’t sure how his thoughts leaked out, but those were the obvious places.

‘Jack.’

‘What?’ Irritated again.

‘What day is it, Jack?’

‘Monday,’ he replied with grim authority, and he glanced at the wall calendar automatically – before he retired, that used to work. One glance and he’d instantly known what day he was in, but what was the point of a calendar now? There were no recent or imminent events, like work meetings or parties, to anchor him to one particular day. He looked at the Chronicle and saw that today was actually Tuesday, but he didn’t correct himself. She’d never know, or if she did, she’d forget in three seconds. Who cared what day it was, anyway?

More than ever, he felt time was the problem. He was leaking not just thoughts, but time, and his life was in disarray as a result. His desk was littered with overdue bills, but hadn’t he just signed the checks to pay them yesterday? Perhaps it was not just himself becoming less solid and certain; perhaps the entire universe was slowly slipping its moorings, like the time his sailboat drifted from the dock into the bay. Perhaps time itself had run amok. That was more bearable, so he held on to this image. A sinking ship meant they were all in the same boat. Lots of company. Good.

‘Monday. Good. A beautiful day!’ she announced, flicking the kitchen venetian blinds open by turning each individual slat. Like the missing pyjama button, this had become normal. They used to talk about repairing or even replacing the blinds.

‘It feels humid again,’ grumbled Jack, not looking up from his pills.

There was that feeling to the day. Oppressive, noisy with birds fretting about the air pressure.

‘It is another beautiful day!’ corrected Milly forcefully. He glanced up, and there it was. Her stubborn face. The fiercely cocked left eyebrow.

‘Beautiful!’ She spat the word at him.

Jack ignored her, focused on the pills. Hadn’t he already taken that pink one?

‘You’re just tired,’ accused Milly. ‘Why do you stay up so late?’

He remembered last night vaguely. His reluctance to end the day – well, of course. How many more days did he have? He wondered why Milly always wanted to rush to the end of the day, closing blinds early, going to bed by nine.

‘Me, tired! I’m not the one getting up in the middle of the night to eat yoghurt! And God knows what else. Didn’t we have a whole loaf of raisin bread? Milly?’

She ignored him, brushing crumbs from the counter to the floor for the dogs.

Jack and Milly were lucky. They could see Mount Tamalpais from their living room window, San Francisco Bay was half a block away, and their street was leafy and quiet. Once there’d been a chicken farm right here. Milly liked to remember this fact. A time when their house was just a marshy field full of hens and rickety sheds. Other houses were close, but it still felt private here. Their world had only them in it. And the ghosts of King and Jaspy.

‘Sam! I mean Jaspy! I mean Jack! Jack!’

Names felt like random odd socks to Milly. She knew they each belonged to one particular other, but she was in a hurry, darn it. She grabbed the name that came to her easiest, and sometimes that happened to be the name of a child or a dead dog.

‘Jack! Do you hear me?’

Jack was almost done. Two more pills, and that would be that. His plan was hatching now, and he almost smiled. Funny how having a project – any kind of project – was so cheering. The day ahead beckoned, and he swallowed the last pills with mango juice. It tasted sweet and cold: delicious. He hadn’t noticed this earlier. In fact, everything was shifting now. It was almost imperceptible, but there it was. Everything had a tingly halo around it, even the sound of the morning radio, the appearance of his wife, the smell of the burnt toast. The house itself was vibrating with foreknowledge.

Today will be different.

For years now, Jack had been conscious of a waiting sensation. All day, every day, he’d been waiting for their lives to get back to normal. Never mind that his old life drove him half crazy, the way the checkbook never balanced, Milly cooking meatloaf three times a week, the dogs never doing what he told them to do. That was normal, and normality was what he yearned for now. Having a plan, no matter how bizarre the plan, tasted like normality to Jack. He was in control again.

‘Jack!’ she shouted again. That man was so deaf.

‘Whath ith it?’ His tongue was suddenly furry and swollen, and the words came out thick as molasses.

‘Where. Are. The. Dogs.’

‘The thog’s er thead, Milly.’

‘What’s wrong with you?’ she asked. He asked himself the same question. Was he drunk? He had to concentrate, remember if that amazing martini he made recently was as recently as five minutes ago. No, no, it was just more post-stroke crap. He took a deep breath and corralled his tongue. So annoying. You think you’re in an ordinary day, then wham. Some days he drooled. Some days his left eyelid only opened halfway till lunch time.

‘I thaid. The thogs. Er thead.’

‘Oh! I knew that!’ Angry at herself again.

‘Courthe you thid, tharling. I knew thath thoo.’

‘I just told you that! You always have to be right, don’t you?’

Jack smirked and sighed. The woozy feeling hovered about an inch from his skull. Would it descend and engulf him? Some days he woke inside this cloud of fug, other days merely slipped into it, then out. Like a seal bobbing in some waves, gasping for oxygen. Now and then he still got rushes of energy, when he thought all things were still possible, if he could just get his teeth in and shave. He’d buy a new hat. A nice grey Fedora, or a soft brown trilby. Nothing like a new hat to perk a man up. Then he’d go to the Montecito Travel Agency and walk out with a plane ticket tucked into his wallet. If the damn agency was still there – last time he looked, not only couldn’t he find it, but the teenage boy he asked had never heard of it. And come to think of it, did men wear hats any more? On what day had men stopped thinking they looked great in hats? He sighed again, remembering how putting on a hat used to make him feel ready for anything.

‘I guess that means I don’t have to feed the dogs then.’ She sighed.

‘I guess not. No more feeding the dogs.’ No lisping this time, whew! Come home to Daddy, tongue.

‘As if you would. Even if they were alive, I mean. As if you ever did.’

Then a giggle snuck into their eyes, but they didn’t give it away. No, no! It was automatic, this withholding of pleasure from each other as long as possible. The smiles resided quietly in the corners of their softly puckered mouths. Their yellowing eyes.

‘Hey, you think it’s easy being perfect? It’s lonely, I tell you, lonely as hell out here,’ said Jack, staring her down, and she surrendered at last. That old girly giggle.

Bless her; it was so easy to make her happy. And wasn’t that forgetfulness of hers also a blessing for him? She forgot all his misdemeanours hourly, and kept sliding back to her original adoration of him. In her brighter days, she could sulk for entire weeks. Once, when she was about twenty-five she didn’t speak to him for almost a month.

But wait. Her face was changing again. He could watch her thoughts flit through her mind as easily as if she was speaking out loud. Oh no, here we go again, he thought. The cocked eyebrow, the look.

‘Did you return Elisabeth’s call?’

‘You never said she called.’

‘I told you, Jack. Three times, I told you.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Would I lie?’

Thinking about his daughter, the great idea drifted off. He’d had the idea before; it was a fantasy, a comforting dream. He’d even attempted it once and failed. Besides, his bowel movement was calling, and all other thoughts (even about his da

ughter) were shunted to the side. Who could have predicted that one day the high point of his day would be a crap? Perversely, it could also be the most hellish part of the day. Excruciation followed by bliss. An accomplished bowel movement was like the first time he sat in the driver’s seat and really opened up the Singer, hit a hundred miles an hour. The Singer scream. One thing was for sure: bowels were king. Jack never ever messed with them. Off he toddled to the bathroom, like a sinful Catholic to confession. He took the newspaper and then picked up a pen in case he had to resort to the crossword.

So another morning was lived through. It was hot already. The windows throughout the house were open, but there was no breeze.

Jack’s Glenmorangie glass from last night, his wine glass and his martini glass, were stacked in the decrepit dishwasher with the breakfast dishes. With great difficulty, clothes were dragged on for the millionth time, teeth were inserted, tears were cried, ringing phones were answered.

‘Hello, daughter!’ Jack said, in his usual affectionate but ironic tone. She was his only daughter – set against his five sons (if you counted Louise’s boys and his son with Colette, and he did). Right now, he loved having a daughter so much, he used the word with gusto. The boys were so much less…well, satisfying. He found their lack of achievement humiliating, and their overachievement threatening. A daughter could be flirted with, and flirting was Jack’s hobby.

‘Yes, yes,’ he was saying to Elisabeth. ‘No, the doctor said I’m plant now.’

‘What? I did not. I said I’m fine now. Why would I say I was a plant?’

‘No, it was not another heart attack, it was another stroke. A mini-stroke. A micro-mini. An episode is what he actually called it. Ep. I. Sode. Like The Simpsons. Don’t worry.’

The sheer effort of speaking clearly was making him sweat, making his chest hurt, and also there was a strange new sensation in his left buttock. Not quite pain, but distracting. Irritating!

‘No, the hospital was not a pleasant place. What? No, I checked myself out yesterday. Called a taxi.’

‘What?’ The novelty of a daughter was starting to wear off again. The boys were never this nosey. In fact, it was quite appealing, the way they mostly just ignored him.

‘Your mother is fine.’

‘Fine, I said! Aren’t you, Milly?’

‘Oh, she’s not here now. Creepy how she just disappears.’

‘Yes, yes. We are both taking all the right pills.’

‘Yes, we did. Thank you very much, daughter. Clever idea, having the days of the week on each little pill compartment.’

‘Yeah, yeah. No, I am not being sarcastic. I haven’t thrown it away! Going to start using it next week.’

Who did she think she was, Florence friggin Nightingale? Then, because this kind of thinking always led to remorse:

‘Listen honey, why don’t you come for dinner soon? Bring the kids. Bring your grandkids! Tell your brothers. Tell everyone, I’ll barbecue.’

‘Tomorrow?’ Too soon! The floors needed to be mopped and the bathroom fumigated. ‘Tomorrow’s not good. Can you come later in the week? Friday maybe?’

‘Because I’m busy tomorrow, that’s why.’

‘Busy doing stuff.’

‘Stuff, I said! You think you’re the only one with a life? I have a life, okay?’

‘No. Not just solitaire on the computer. Yeah. Friday it is, then. Goodbye, Elisabeth. Goodbye! Goodbye!’

He hung up with a mixture of anxiety and irritation and something else he could never put a name to, but made his throat feel funny. Damn her! Just his luck to have a conscientious daughter. Strange how he was afraid of his kids finding his house in a mess. When did that switch round? But then they had the power to pull the plug. No one ever told him how just plain humiliating it was when you got near death. Just when you could least deal with it, there it was, slap bang on your doorstep. Like a continual day of being caught shoplifting condoms, of losing erections, of wet farting on a first date. No two ways about it, getting this old was basically one helluva hangover without the memory of a fabulous night before. His incompetent scatterbrained daughter telling him what to do was the final blow.

He was jealous of his neighbour and old friend Ernie, who was the same age. None of his kids gave a damn. And his wife, Bernice, still cooked great dinners, every damn night. And still drove. Probably still gave him blow jobs. He bet she never asked Ernie what day it was, or demanded he buy Tena Pull Ups at Walmart, that cavernous hell. But then he remembered a conversation from last week, or last year – it was hard to tell – and Ernie had said, You always think my marriage is perfect. That we never fight. Are you insane?

‘Elisabeth! Get down from that table right now!’ Milly suddenly barked to her four-year-old daughter, who for a moment was visible, in those soft pink Oshkosh dun-garees she’d loved so much about sixty years ago. Then, because her shout had dispelled the child, Milly smiled goofily, embarrassed.

‘Jack? Jack?’ Hoping he hadn’t heard her crazy shout. ‘Good,’ she said aloud to the empty room. He must be in his office still. ‘That man is so deaf!’ And then she giggled, because what had just happened struck her as hilarious. She made herself laugh again! What excellent company she was. She giggled on and off for a good five minutes, because even the fact of her laughter struck her as funny now. The way it hiccupped a bit, just like her grandmother’s.

No two ways about it: Milly was a bit dippy. Even she knew it. There’d been no dramatic dip into dippy-ness, no particular day or event that led her family to frown and say: Oh no! Milly is off her head! But here it was now, craziness as solid a part of herself as her cocked left eyebrow and her yellowing toenails. Her mind was like a weather report. Cloudy intervals, with occasional clear warm afternoons. Now and then green clouds with polar bears riding them.

Still, the bigger truth was that, crippled or not, senile or not, Milly remained the guardian of this house. Punctual and reliable in the extreme. Morning and night: unlocking and locking doors, opening and closing each venetian blind. The bed sheets were only changed by her, and only she knew when it was time to buy more toilet paper. She was pretty certain they had never run out of milk. She’d been the guardian of this house for over fifty years. It had been a new house then, so if the house had a consciousness (and in her opinion it did), it belonged utterly to Milly. No other mistress haunting the corridors. It would obey no other queen. If you could marry houses, Milly would have divorced Jack years ago.

Jack turned on his computer and began a game of solitaire. Milly walked down the long hall to the bathroom. A journey of seven minutes, but her bowels were her friend, so actual toilet time was a fraction of her husband’s. Then she returned to her chair in the living room. A three-point turn in order to drop her bottom on the seat. Her kids wanted her to get a wheelchair. What did they know? In this respect, they were the enemy and she ignored them. Heaven’s sake, it was only those old broken bones. She spent the rest of the afternoon keeping Jack on her radar by noise and intuition. Garage? Bathroom? In some floozy’s kitchen drinking gin? No, no, that had only been a short phase, long gone. Jack was a faithful man, a good man, with a bit of mid-life nonsense on his CV. Now…had he eaten his fruit, taken his vitamins, put on clean socks?

The dogs were also on her radar – she kept glancing down to the places where they used to sleep, and where their food dishes had been. She did this in the same reflex way she’d checked her babies were breathing, and later, that they were still in the yard, or still in their rooms. For years after the youngest left home, she’d kept waking at night and panicking, till she remembered their new addresses and phone numbers safely stored in her address book. A radar out of range of its objects, she couldn’t stop reaching out for her children in a visceral way, every minute of the day as if one of her organs – her heart? her thorax? – had developed searching tendrils. Darn those kids! They’d better be wearing sun cream today, look at that sun!

Milly kept her family safe. That was her

job, and she could not stop doing it for love or money. This memory problem was a mere hiccup, an annoying blip. Like her vision dimming, but never badly enough to incapacitate. Like the way her left leg had slowly ceased to obey, but still let her get around on her own. She said no to taking her own limitations seriously. That way lay defeat, and she certainly didn’t want pity. No, no, no. She was still needed, so tethered herself relentlessly to her charges. Or charge.

‘Jack!’

‘Jack!’

‘Jack!’

‘What is it?’ Angrily. The computer was winning.

‘I have four thirty. What do you make it?’

‘Jesus, Milly.’

‘I said, I have…’

‘Four thirty. Four thirty, okay!’

‘It’s four thirty already?’

The days flew by so quickly, so painlessly. She really didn’t know what all the fuss was about. Getting old was a breeze. After checking her watch once more, and telling herself she’d rise in thirty minutes to close the blinds, she sat in her window seat and re-entered her dreams. And what did she dream about for the next half hour? It was a patchwork of things around her and things that had happened – the gulls crying, the smell of eucalyptus, the classical FM radio music, all the birthday parties she’d ever given for her children, the cupcakes she’d made for PTA sales, the Halloween costumes she’d sewed, the trips to San Francisco for the sales, the way chocolate milkshakes tasted at Courthouse Creamery, the way the waitress used to give them the silver shaker with the remainder of the shake to pour out themselves. The coffees another waitress used to bring herself and Harold, even though they hated coffee. The splinters in her bottom from the deck that scary morning, with Jeff looming over her and Mister Rogers on the television. The taste of Jack’s skin after a sail. (A small smile at this.) Harold’s nose in profile, like a Roman. Her hand briefly in his, in the dark theatre. Then up popped that favourite pair of cream gloves she’d worn to church all the time, and where had the left one gone? Under a pew? And her wedding ring too, where had that got to? Thick gold band, with rubies inset. Oh, her throat swelled, remembering these lost loved items. Her children, her babies – she missed them too. Darling Charlie sliced into her chest, cold in his crib with the decals of Bambi. Then she kissed his forehead, bowed away from him and thought about the way her children were all so different. Like Jack, she included Louise’s boys as her own children, and as an afterthought, darn Colette’s son too. She spent whole minutes just contemplating their very different hair colours. A sudden memory of Sam in his Senior Prom suit, face freshly scrubbed with dabs of Clearasil on his forehead and nose. Oh, how those flesh-tinted dabs had torn at her! And that hat she’d bought Elisabeth once, to wear to Easter Sunday Mass. White straw, and it had gone so well with her pink seersucker dress, hadn’t she been a picture? Her heart swelled with pride now. Satisfaction for a day well executed. And wasn’t that exactly how it had been, for all those years? Her moody children, her wayward husband – just normal people, all of them – with her on the podium waving a baton, conducting their lives into some semblance of order and safety and…attractive appearance. Oh, the thrill on the rare days when they all seemed to obey!

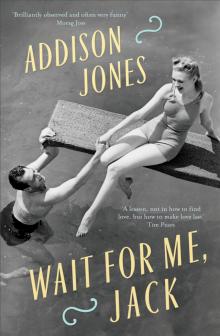

Wait For Me Jack

Wait For Me Jack