- Home

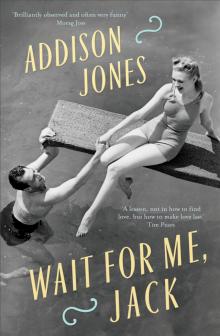

- Addison Jones

Wait For Me Jack Page 3

Wait For Me Jack Read online

Page 3

Even now, in her daydreams, she wanted to photograph those moments. To run and find her camera, but by the time she was ready the moment had passed. The ice cream had melted, the arguing had recommenced, the cloud moved over the sun.

It was strangely difficult to access any specific memory, but these unasked for memories just bubbled up. Her face was peaceful, slack. If she was homesick for those years of raising children, of handmade cards sticky with syrup, of Lego under the sofa, of midnight bedwetting, of those small bodies always pressed against hers, it was such a constant state she didn’t interpret it as homesickness. In any case, homesickness, like love, took energy, and this was something Milly did not have a lot of. Despite centuries of literature and music proclaiming otherwise, Milly knew that love was not what remained when everything else was stripped away. What remained was an awareness that love had been. Milly needed every ounce of energy to get out of bed in the morning, and repeat the essential routines of daily life.

When she surfaced, it was exactly five o’clock.

First thought: Close the blinds.

Second: Where is Jack?

Third: Have the dogs been fed?

Fourth: Are the children all right?

Fifth: When will I see them?

These last two were wistful, thin thoughts, and evaporated within seconds. Not like numbers one, two and three, which were on a constant loop.

She rose slowly from her chair and closed down the house. Flicked each venetian blind down, switched on lamps, looked for dog food then remembered. Did the pepper grinder need more peppercorns already? Gosh darn it.

‘Jack! Jack!’

‘What is it?’ Still losing at solitaire to the computer, in between naps in his chair. Computers cheated, obviously.

‘Come here, please. I need you to open the pepper grinder.’

‘I’m busy, Milly. In a minute, okay?’

‘Oh, to hell with you,’ she said, leaning on the table, the grinder in one clenched fist.

At the periphery of her vision were all the people who wandered her house from time to time. When she was anxious or angry, like now, they tended to creep a little closer to centre stage. (Not quite like her vision of four-year-old Elisabeth in her Oshkosh overalls, or the way she’d hallucinated her sister, Louise, for a few weeks, a million years ago.) She didn’t know these folk. And no, they did not frighten her; they seemed a friendly lot, placidly walking around her rooms, intent on getting somewhere for some ordinary task. To the store for milk and bread; to the garden to pull weeds; to the hall closet for clean towels. Yes, she understood they couldn’t exist, and, yes, she also knew not to mention them to Jack any more. He dismissed them as urinary infection hallucinations.

Secretly, she believed they might have an existence. She’d become fond of a few in particular, a small boy and a fat old woman. Some days she convinced herself the boy was her baby Charlie, grown seven years older, and the fat woman could be her long-lost sister, Louise, grown old. Loulou had always run to fat. They looked her in the eyes, unlike the others, so if they existed perhaps they had a fondness for her too. They didn’t talk, but their presence was calming. Maybe they were in the future, and to them, she was the ghostly figure that couldn’t rationally exist. Perhaps, she thought, her loneliness had pulled them out of thin air for company. Perhaps they already existed, and her eyesight had developed somewhat. As if the older she got the thinner the membrane between herself and an afterlife. They’d been around for about a year now, and were hardly worth noting any more. Part of the furniture, so to speak.

After they had dinner, microwaved macaroni cheese, Milly made the treacherous journey from table to dishwasher, while holding on to both her walker and an expensive plate. Sometimes she put items on the floor and gently slid them along with her feet. Sometimes she used her mouth for carrying things, like dishcloths and newspapers. But plates were just too heavy, not to mention slippery. She took the plates one at a time, and nudged the walker along with her lower arms and elbows. If Jack was asked how his crippled, partially sighted wife managed to set and clear the table, serve meals, make their bed, do the laundry, he would shrug and laugh like a naughty boy. I have no idea! he’d say gleefully, and it was true. He’d rarely witnessed her doing these daily tasks. He was a busy man, and anyway – what else did she spend her days doing? What bills had she paid? What job had she spent fifty years working at?

Milly, Jack often said, was getting away with murder.

The kitchen radio was on, as usual, and tuned to Classic FM – not because they particularly liked classical music but because it was a new digital radio, and they’d given up figuring it out. A rogue programmer had allowed an old Billie Holliday to slip in between Mozart and Chopin. If I should take a notion, to jump into the ocean. Milly inserted the last dirty dish – Jack’s dinner plate – into the dishwasher, and then with a melodramatic arm gesture, as if sweeping away hordes of admirers, she said: ‘Wa!’ to the empty kitchen. The walking folk scattered instantly and disappeared like a spray of water on a hot sidewalk. What she meant by this odd syllable – by Wa – was a combination of voilà and moi. Wa meant: This is me! The best of me I’ve got. Take me or leave me, darn you.

Milly said Wa! a lot, but Billie Holliday had caused this particular Wa.

She’d always been susceptible to certain music. Classical music had no nostalgia for her; it was neutral, impersonal noise. But this! If I go to church on Sunday, then cabaret all day Monday, it ain’t nobody’s business if I do. She had no defence against this. She closed her eyes and recalled dancing. Like her grandchildren’s fingers twitching in the correct sequence when they were imagining texting someone. Her day to day memory was poor, but her muscles had an excellent memory. The swing of her left foot now, the sliding, the twirling, the precise flying feel of her arms as they floated in the air to the sad defiant music.

I swear I won’t call no copper, if I’m beat up by my poppa.

Her eyes squeezed shut. Pretending to dance always brought a wave of sweetness and melancholy. Too much, and when the song ended, she was limp.

‘Hey. Honey. Milly.’

‘Jack! How long have you been standing there? Did you need something?’

‘What were you doing?’

‘Nothing. What do you mean?’

‘I saw you.’

And this was when his great idea trickled back in. A good husband might flirt with other women, but he did not leave his wife. Milly was his person. He fell in love with her all over again, as if he’d just met her. Tears welled up.

‘So?’

‘Were you, sort of, dancing?’ His voice cracked on the last word.

‘What? Are you bananas?’ A full face frown. Eyebrows, mouth, nose, jaw.

‘You were, weren’t you?’

After a pause, Milly said primly: ‘I was thinking about dancing. I was remembering. But how did you know?’

‘Just the way you shut your eyes. And you kind of rocked. A bit.’

‘Did I?’

‘And smiled too.’

Milly glared, then said: ‘Oh, come here, you.’

‘No, you’ll hurt me. You’ll tickle me.’

‘Don’t be silly. I am not the one who tickles.’

‘You were a wonderful dancer, sweetheart.’ In fact, he had vivid recall of all the men’s eyes on her, while she spun round some ballroom – Larkspur Landing? That red dress with the orange sequins. New Year’s Eve, 1951. Boy, he married a beauty all right.

‘I know.’

‘I was a terrible dancer,’ he said.

‘I know.’

The ballroom image wouldn’t go away now. ‘I don’t know how you stood me, dancing with you.’

‘Well! We didn’t do it very often, did we?’

‘No.’

‘Come here right now, Mister Jacko MacAlister.’

‘You’re so bossy! All right then, Miss Billie Mae Molinelli. For one minute.’

She let go of her walker, he took her

weight, and miracle of miracles – what was going on today at Classic FM? – the next song was ‘In the Mood’, Glen Miller.

Who’s the loving daddy with the beautiful eyes?

What a pair of lips, I’d like to try ’em for size…

It occurred to Jack that Classic FM would never make a mistake like this; never play old jazz. Was it the radio’s fault, or their own? Then it occurred to him that marriage might be a bit like dancing to radio music. You didn’t know what song you’d get next. First you’d be with your partner, happily dancing and thinking – Yes, I get it, and it’s good to be here. I know this kind of music. Look at us – just like everyone else! Then a song might start up that you didn’t expect, and didn’t much like. Maybe the sax player squeaked, the pianist sounded flat, and someone was singing the same three jarring lines over and over – so irritating! You’d keep dancing, but now you’d be thinking: Actually, this isn’t much fun any more. Five minutes later, you’d think: This is hell. When will this song end? I can’t stand much more of this. Then suddenly, there’d be an old much-loved song, like this one playing right now.

And I said: Hey baby, it’s a quarter to three,

There’s a mess of moonlight, won’t-cha share it with me?

Such a relief to be on familiar ground again, it reminded you why you married in the first place.

They danced without moving their feet. At first he let her lead, and followed the swaying of her torso, let her hug him tight, rest her head under his chin. Hey, what the hell? She’d shrunk! That would explain her skin being so loose.

First I held him lightly, and we started to dance.

Then I held him tightly, what a dreamy romance.

‘So,’ said Milly softly. ‘What will we do now?’

‘What do you mean?’

She had to think a moment, how to explain herself.

‘I mean, what happens next? What do we do now?’

It was still an oblique query, but he understood. What was there left to do, in the face of imminent death? It was so in tune with his own thinking today, tears welled up again. It was heaven, now and then, to be understood by his wife.

‘Well?’

‘I’m thinking, sweetie.’

‘Well?’

‘As long as we can keep dancing, Milly, I think that’s what we should do. Dance.’

‘But I can’t dance, silly man.’

‘Shush,’ he whispered. ‘Just dance.’

Pause.

‘If that’s all there is my friend, then let’s keep dancing,’ she sang into his chest. ‘Remember that song, Jack?’

‘Yeah. Shush, now.’

‘It’s such a corny song.’

‘I know, I hated it.’

‘Me too.’

When the chorus began, Jack took her left hand and held it to his chest, and led her in his own rhythm. In the mood for all his kissing, in the mood for his crazy loving.

And for a minute it worked. Then he missed a beat, and another, and she began to snort with giggles, which brought tears to her eyes. In his entire life, he’d never met a woman whose laughter could literally leak out of her eyes.

‘Oh, forget it,’ she said. ‘I’ve got things to do.’

‘Aw, come on, Milly. Give me another chance.’

‘You’re going to make me fall.’

‘I love you, Milly.’

‘I know.’

‘No, I mean I really love you.’

‘Okay. We’re almost out of dishwasher tablets.’

She moved away from him, gripped her walker. He noticed the pee smell again, but this time it was not repulsive. All he wanted was to hold her again, but she was fussing with the butter dish now, trying to close the lid.

Jack suddenly remembered taking her to the Sutro Baths, that first summer. Her red bathing suit, the way her skin looked milky against it. It was the pool’s last season, though no one knew that. Six salt water pools fed by the nearby Pacific Ocean, over five hundred changing rooms, and little refreshment bars scattered everywhere with names like Dive Inn. The high curved glass ceiling beamed down sunlight and bounced voices and splashes: a constant racket of delight. There were rings to swing from into the water, but what he remembered most was showing off his dives from the only diving board. He’d learned to dive by jumping off a rock into Sonoma Creek the summer he was fifteen, and he was proud. The way he used to cut cleanly into the water and surface like a seal. But at the Sutro Baths, with the bracing green Pacific below him, he remembered feeling awkward because she was watching in her red bathing suit. He worried he’d be clumsy, and then he worried that being worried would make him clumsier, because grace (he’d learned) had to be instinctive. But it was all right, and when he surfaced and looked for her face, there it was, smiling at him as if he’d just won an Olympic gold medal. Something so naked about her admiration. It was better than getting drunk.

He’d tried teaching her how to dive, but she was surprisingly inept. She kept freezing at the last second and bellyflopping. She laughed, but he could tell it hurt. Much later, because the pool was almost empty, she just sat on the diving board and swung her pretty legs. He was treading water below and they talked. Talked and talked, and treading water was so effortless he felt he’d never sink as long as he could keep talking to her.

‘A matter of weeks, Jack,’ his doctor had said yesterday, sitting by his hospital bed. ‘Or maybe months, but not six. Have you looked into hiring a home care nurse? Or entering a care facility? Or hospice care? I can help arrange that.’

‘Fuck off.’

‘What?’

‘My cough. It’s getting better.’

Jack could have done without the light banter about summer vacations immediately after the diagnosis. Like discussing what a great party it was going to be, what a pity you weren’t invited.

He poured a brandy and port, took it to the living room and turned the television on to PBS. Inspector Morse and Sergeant Lewis were sitting at the Oxford high table suspecting murderers, but Jack was visualising this: the children, all six of them plus their spouses, would arrive on Friday. The shocking discovery would be shared. They’d come straight in, no door knocking in this family. They’d notice how clean the house was and wonder if a cleaner had finally been hired. They’d walk around, calling: Mom? Dad? Grandma? Grandpa? Or in Danny, Donald and August’s case: Jack? Milly? Anybody home?

After peeking into the other rooms, they’d peek into the master bedroom and at first they’d think they were asleep, all curled up. He was so enamoured of this scene, he edited it and replayed it, with different night clothes, times of evening, lateral poses. Perhaps the remnants of the wood fire would linger, covering any unpleasant odours. Stink would ruin the mood. Got to get it right. This reminded him of all those early imperfect ragged manuscripts, the ones he’d sensed containing a germ of genius. The way he’d tweaked them and carved them, chosen the perfect cover, the best quality paper, the right blurb for the back sleeve. Goddammit, he’d been the genius, not the author. Actually, the whole of life had been a rough draft, just waiting for his expert editing, his instinct for what people really wanted. If he’d ever got around to writing that damn novel, it would have been the best masterpiece in the history of literature. It would have, once and for all, pinned down his generation. More intellectual than Dos Passos, more perceptive about women than Hemingway. If he’d had time.

He remembered the fiasco last autumn after his heart attack and just before he lost his licence.

‘Come on, Milly,’ he’d said. ‘We’ll drive out to Hawk Hill. You always love that drive.’

All the way there, he’d kept rehearsing how he’d put on her favourite CD, and his too. The Harry James Orchestra, You Made Me Love You. Then when they got to the bit of Pt Bonita Road where nothing lay between them and the Pacific Ocean, he’d say: Close your eyes a minute darling. I love you, Milly. You’re the best. Then he’d close his own eyes too, and gun it. Shoot them both over the cliff, and sure it’

d be scary and they’d probably scream, but then it would be over within seconds. He’d been very curious about what the car would do, mid-air. He hoped they’d remain in it, right side up. Not upside down. It would be terrible if one of them fell out of their seat while the other watched.

But at Corte Madera, Milly had started demanding they find a bathroom.

‘Just do it where you are. That’s the whole point of diapers.’

‘I do not pee in my underpants, and I do not wear diapers. Are you crazy? Stop the car now!’

He’d finally stopped the car at a cafe in Sausalito, and ended up ordering coffee and carrot cake for them both. By the time they’d finished, the urgency had drained away and he’d driven them home again. Milly hadn’t even noticed the cancellation of Hawk Hill. Just sang along with Harry James, happy as a clam, even prettily clapping her hands as if they were in a public place and people were watching.

Now Jack thought, Oh hell, why wait till Friday? The house was clean enough, damn it. At least the kitchen was. Let them think what they like. He waited till Milly left the kitchen and was making her way to the living room to watch the ten o’clock news.

Wait For Me Jack

Wait For Me Jack